In our projects we focus on telling meaningful stories rather than just engineering pretty layouts. This approach has attracted critical acclaim from clients, journalists and design critics alike.

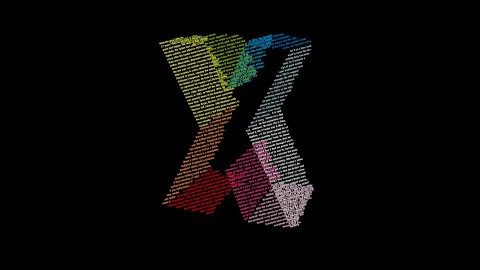

Carnival

The result is a riot of words and colours jostling with each other for attention, like a carnival in a paint factory.

Read more …

True Colours

How do you create an effective identity when the company’s business keeps changing to stay in line with new technology? Steve Shipside examines Thomas Manss & Company’s work for Laserbureau.

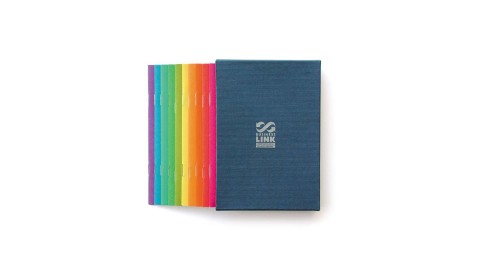

“You can have all the colours you want, but don’t come back with any cool designer nonsense.” No, not Henry Ford the morning after, but Joe Brim, owner of Laserbureau, briefing a designer on the creation of an new corporate identity. Laserbureau is a technology production company servicing ad agencies, design companies and the like. The unlimited colour promised by Brim comes courtesy of Laserbureau’s in-house technology. However, if the technology removed the colour barrier, it posed a problem of its own. Where once Laserbureau was content to run out bromides, it has since embraced new technology with a passion. Encompassing all of that presented quite a chalenge to the designer, Thomas Manss. “The client said ‘We need a new logo to present what we’re doing,’ so I said ‘what are you doing?’, He replied ‘oh, that changes every four weeks.’ So a static logo would have been a problem.”

Manss doesn’t look as if he was particularly daunted by this. He first came to the attention of Laserbureau as a customer. He clearly made an imression because a year and a half later they called him to ask if he could help with their new image. He certainly agreed that they needed one. The solution that Manss hit on was to take Laserbureau owner Joe Brim at his word, and give a feeling for the breadth of the services offered by the company. Since those services could be changed at any moment the design was intended to make it easy to adapt. The result is a riot of words and colours jostling with each other for attention, like a carnival in a paint factory. “Yes, it seemed safely outrageous… and in the end such an enthusiastic business card is perfect for Joe.” Colours were: “whatever you can do in the four colour process – there is no house colour.” Manss acknowledges that the Latin American flavour of the result may owe a little to work he did for the Hotel Arts Barcenlona, which was equally vivid. As for fonts, Futura was selected, but as Manss explains, the brashness of the design left him with little choice in that department. “I tried a few other fonts but what we needed was maximum ink coverage and you need really bold fonts for these pattern – you can’t use an nice Swift face. Futura seems the best choice for such a fat face.”

The design also had to work large or small – it’s now appeared on business cards, folders, letterheads, promotional watches, a billboard, and, most dramatically of all, on a 30 meter long banner running right across the shop fornt in London’s Crawford Street. The flexibility that lets a logo span the gamut from business cards to shop fronts is the key to this particular client’s identity. According to Manss, however, the identity probably has further evolution ahead of it if it’s to keep up. “If they have a new service the can place it in on top.”

Steve Shipside

Graphics International, London, UK

Top Ten

As part of its weekly 'The Top Brass' column ‘The Independent on Sunday' voted Thomas Manss one of the top ten graphic designers in the UK.

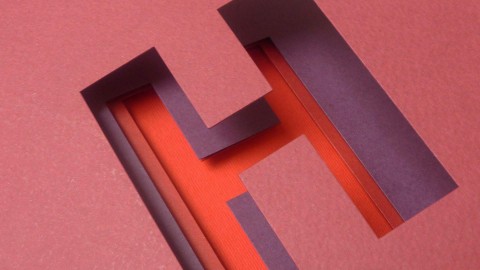

Twist

Thomas Manss & Company’s designs do not pander to fleeting fashions but instead rely on a little twist to make a memorable impression.

Read more …

Being a specialist is all very well, but it won’t win you the decathlon, reckons Deborah Richardson

When asked why he became a graphic designer, Thomas Manss is inclined to quip: “I joined the shorter queue”. He qualifies this with an explanation: despite every intention of following in his parents’ footsteps and becoming an architect, seven years of study and 20-30 more years before a major project would be built had limited appeal. By a quick process of elimination – helped by a shorter line for graphic design at university registration – he found an alternative which would satisfy his inclination to solve intellectual problems visually.

The anecdote reveals a great deal: a ready wit, intuitiveness, an aptitude for paring down a problem to its essentials, quick lateral thinking and an ability to come up with a well-judged solution. In fact, it sums up the work.

If Thomas Manss & Company’s work shows a certain single-mindedness, it is no contradiction that it is exemplary in its diversity. If you liken an identity programme to a decathlon and the designer to a decathlete, you begin to get the idea. It’s no good if you can sprint well but don’t pass the muster in the shot put; likewise you won’t win any medals if your logos are masterful but the web application is weak. As a body of work, the identities, symbols and marks, promotional collateral and annual reports, exhibitions and screen designs in this book demonstrate the decathlete’s skill. They also have that extra magic that makes the performance memorable… and the client the real winner.

Deborah Richardson

Colour

A German designer well-known for his use of colour.

Education

Thomas Manss & Company is not a design company, it is a finishing school for aspiring graphic designers.

Fun

Serious fun is at the heart of Thomas Manss’ success.

Read more …

“Everything you could have nicked from that hotel, we designed,” Thomas Manss explains with a grin. The hotel is in Barcelona, with architecture by Bruce Graham and Frank Gehry, now managed by the Ritz Carlton Group. “The American developer sold the hotel to the Ritz ready to roll, with two years supply of everything – sewing kits, placeholders, menus, and so on – and we designed them all.” But then Manss is no stranger to large-scale projects. When he qualified from design school in Berlin, he went to work for the Berlin office of Sedley Place: “My first client was the German Post Office, the largest employer in Europe, which was after a new identity. The second was Volkswagen. And my friends were starting out with fun stuff – posters for art galleries, letterheads for their chums.”

In 1989 Manss moved to London, to work with Alan Fletcher at Pentagram (“I told Alan that I’d do anything – absolutely anything – except design in Neue Helvetica again”) and four years later opened his own office. An invitation back to Berlin as a visiting professor led to comissions in Germany, and the opening of a Berlin office in 1996. “We have had a lot of foreigners working here, designers from Spain and Holland, even an Zimbabwean with an Italian passport, once. I like the changes of perspective we get from contact with these different cultures – I see myself as a European, not as either British or German – no Perpetua small caps, but not everything at right angles, either.”

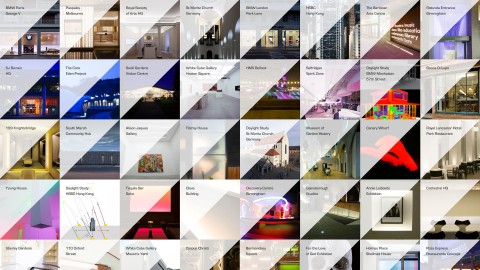

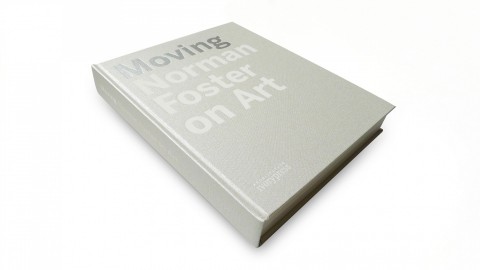

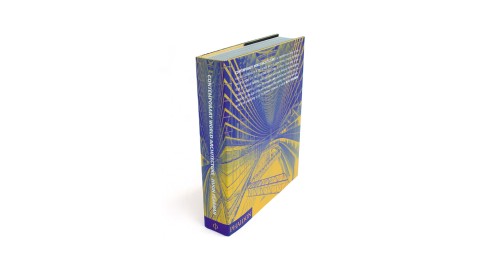

As well as travelling between London and Berlin, as Manss puts it, the company oscillates between corporate work and fun projects. Manss designed the catalogue for the Stirling Wilford exhibition at the RIBA in 1996, and again for Michael Wilford exhibition in Bilbao this year. He has also worked for Michael Hopkins and Partners, and for Nicholas Grimshaw. As well as designing several books for Phaidon, including Hugh Pearman’s recent “Contemporary European Architecture”, Manss has done a number of promotional pieces for Arjo Wiggins Fine Papers, and is currently redesigning the National Art Collection Fund magazine and Annual Report. “But we also do a lot of work for the Institut of Directors,” he points out, “and you can’t get more serious than that.”

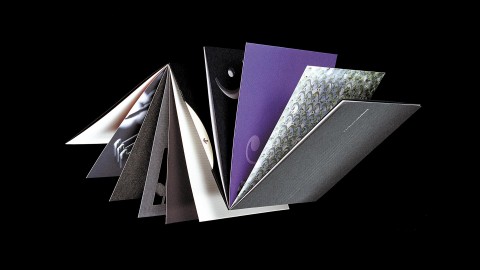

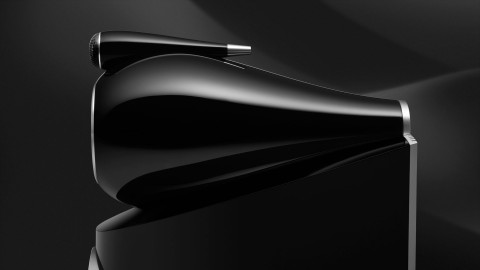

Often one corporate project leads to another: “Because of our core expertise in creating corporate identities,” he explains, “we are often seen as having a broader understanding of the company than the company itself, so we get asked to take on further tasks, such as trade fair stands and sponsored exhibitions. We recently did an identity for the Oberhavel Verkehrsgesellschaft bus company, which in turn led to stationery, then merchandising and sevice cards, and even uniforms.” With B&W, Britain’s most important loudspeaker manufacturer, it was a case of working from the bottom up. Manss was asked to create the branding for Solid, an affordable lifestyle system. His most recent work for them is the brochure for the new Nautilus 800 range: “They said it was the Aston Martin in loudspeaker design, so I modelled the brochure on a car.” Seductive photographs of details (headlamp or horn?) and expanded technical drawings, are presented on heavy A3 paper.

“As I see it, the designer has two tasks,” Manss explains, “the first is to resolve the problem the client has brought to you, and the second ist to make this solution desirable. Call the second part the X-factor or whatever: the way it works is that when you see the design, you want it.” How this operates can be seen in a recent project for Business Link Herefordshire and Worcestershire, a body which offers management advice and services to small and medium-sized businesses. Originally a nationwide Government agency, the service has now been passed to the private sector, in smaller local units. Herefordshire and Worcestershire came to Manss for a new brochure, to replace the previously shiny twentyfour pages of A4. According to Manss, “Business Link had a problem: despite its considerable local experience it was seen as a Government agency. And it had a problem selling it services. I pointed out that what its previous brochure did was to describe the product, not address the problem of Business Links customers. So what we set out to do was to define the real problems its clients had, and the relevant areas of expertise that Business Link had, and so device something to nice to throw away (the X-factor). It rapidly became a collaborative process, in which everyone contributed.” Manss hired a copywriter, Simon Hollingworth, to interview Business Link managers and existing customers, and commissioned a photographer, Nic Gaunt, to take portraits of clients and staff. The resulting material was repackaged, not a single brochure, but as a boxed set of ten twelve page booklets, ten by fifteen centimetres in size. Each booklet deals with a specific topic (such as Workplace, Export, or Manufacturing) and carries a question on the cover: “What do you need to do to maximise the impact of your product or service in the marketplace?” for example on the Marketing booklet. Inside, on the opening page, a broad brush description of the problems and opportunities involved, followed by a spread describing the various services Business Link can offer, then a spread of testimonials. The centre spread discusses the key issues in more detail, before a further spread of testimonials, a spread (reversed out) of comments from experts or specialised magazines on the topic, and a final page of contact details.

This is standard brochure fare, but the way it is organised – questions first, than answers, a way of saying “you” to the reader from the start, not “me” – make it quite different. The visual elements, especially the photography, are als key: the portraits of clients, full page facing the two testimonials pages, show them up to their necks in their work: the sport shoe manager in suit jacket and no trousers, the kitchen maker inside his own cupboard, not to mention the worm farmer. These introduce a lighter note, just as the extracts from magazine articles build in information and not just flannel. But the photographs also carry the message that if existing clients are happy to be portrayed in a fun way, then Business Link is, in a sense, worth taking seriously. The strong colours of the jackets, the punning logos for each booklet cover and the use of dark blue ink on the insides invite the reader in.

The booklets have already had an important influence in changing approaches to customers within Business Link, and are now much in demand by clients. They make the services offered relevant and accessible, through an elegant and economic graphic solution. A Design Effectiveness Award candidate, no doubt. And a fine example of Manss’ serious fun approach to design.

Conway Lloyd Morgan,

Graphics International, London, UK

Humour

Which brings us to the very nub of humour or wit in graphics; it's a valuable means of achieving an instant rapport with the audience.

Read more …

Graphic Wit in Britain and Germany.

Eccentric humour versus no humour – Jim Davies looks at the truth behind the stereotypes.

Southern Europeans stereotypically exhibit natural flair in everything they do. They eat and drink, fight and love, live and die with an uninhibited style and lustiness. Not surprisingly, this appetite for life spills over into their design. Move further northwards up the map of Europe, however, and national characteristics begin to shift. By the time you reach the less temperate climes of Germany and Britain, the vaunted excitable tendencies of the southern Europeans have all but disappeared. Where the Germans have a reputation for clinical efficiency and rigorous organisation, the British have one for shambolic eccentricity and charming self-deprecation. Though both nations have equally complex and subtle languages which lend themselves to sophisticated word play, German humour, some might argue, is a contradiction in terms. British humour, on the other hand, has a long and glorious reputation – self-flagellants each and every one, they simply can’t resist poking fun at themselves. So how do these entrenched national traits manifest themselves in graphic design?

Humour in design is an art, not a procedure. Like all jokes, the basis of graphic design humour is the unexpected – turning a letterform on its side, for instance, so that it becomes a pictogram of a table, or combining an image of a fish with an inappropriate word like “moo”. It will rarely make anyone roll about with mirth, but it may force a smile or engender a feeling of collusion between designer and audience. “Wit” or “playfulness” are perhaps better words to describe the level of humour in this context.

Thomas Manss is a German graphic designer with studios in London and Berlin, and a visiting lecturer in corporate identity at the Fachhochschule Potsdam. He is perfectly positioned to assess the differences in graphic wit apparent in the two countries. “First I will support the prejudice that Germans don’t have a sense of humour”, he says, nipping to the back of the studio to retrieve a pile of corporate identity manuals for Volkswagen, one of the first projects he worked on after leaving college.

To say they are thorough would be to do them an injustice. No stone, no grain of sand even, has been left unturned. There is a tome on the correct positioning of the VW logo in every conceivable size and manifestation; another volume on house colour; another on stationery; how to photograph your product; here’s one on corporate signage; yet another on overhead projections. But the manual on how to paint your factory the VW way takes the biscuit. It contains gems like “all moving parts of machines and equipment must be RAL 2001 red-orange”. Sure enough, there were very few belly laughs to be found around here.

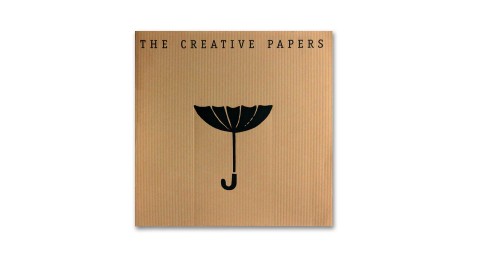

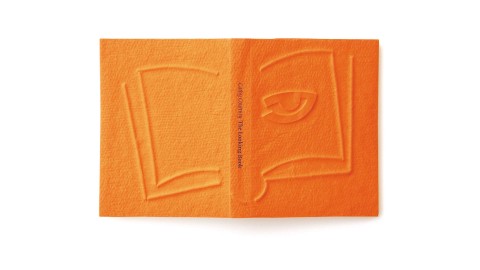

“In bad times, it’s quite good to be German”, maintains Manss. “When times are good, you want an Italian car – ok, it may not work that well, but it looks great. When there is a recession on, you have to be sensible and play safe, so you buy a German car because you know it will be reliable however bad the weather.” The analogy, he continues, also applies to graphic design; when belts are tightened, clients prefer to avoid risk by sticking to tried and tested graphic solutions. Humour is regarded as flippant and inappropriate, and a sensible, po-faced approach to design tends to prevail. Once again, it’s time to wheel on the Germans. But there’s a twist in the tale. Manss reckons he can get away with slipping more humour into his design projects simply because he is German. “Some clients think, ‘Well, if a German thinks it’s ok, then surely we can get away with it.’” A case in point is Manss’s promotional work for British paper manufacturer Arjo Wiggins Fine Papers’ Range of Creative Papers. Opening up like an old-style 12-inch record cover, the sleeve houses a series of square cards on different types of paper. Each bears a clever visual joke, which at the same time manages to highlight a particular quality of the paper.

One of the best is on the cover itself, an inverted umbrella “for catching rain in dry countries”: Printed on a ribbed paper, the area immediately underneath the brolly has been debossed, as if it were actually stopping the rain from falling beneath it. The set of images are designed to be used by salespeople as both props and promptcards; sharing these ready-made jokes with a potential client has proved a successful tool.

Which brings us to the very nub of humour or wit in graphics; it’s a valuable means of achieving an instant rapport with the audience. Having caught their attention, the more serious business of educating, informing, or selling can begin in earnest.

Jim Davies

Print, New York, US

Impact

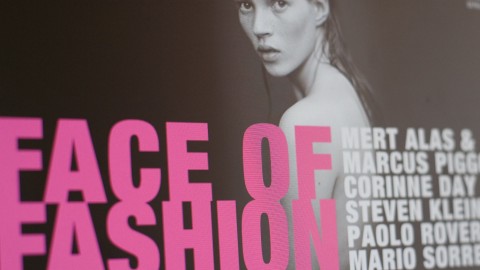

Judges described the National Portrait Gallery's Face of Fashion campaign as "very well executed, with high impact and strong stand-out". The jury was particularly impressed by its "elegance, strong use of typography and arresting use of images".

Integrity

The jury commended the integrity of the overall concept, that clearly visualises consistent thinking. The successful 'play with graphic constants and variables' deserves a special mention.

Masterful

The masterful layout by Thomas Manss is full of silent subtleties.

Media

I was constantly impressed at Thomas Manss & Company’s ability to translate the same message consistently across radically different media.

Narrators

Thomas Manss & Company are designers, but they are also – and more importantly – narrators, myth-makers, fabulators, tellers of tales.

Ordnung

We need a teutonic sense of ordnung whilst longing for a splash of English eccentricity.

Read more …

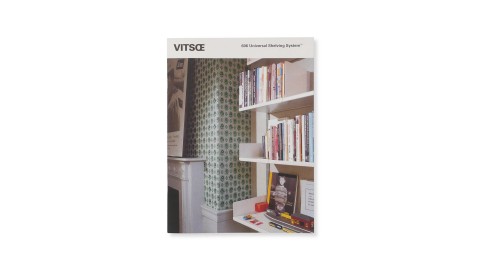

Teutonic Ordnung or English Excentricity – Vitsoe's Mark Adams finds them both.

Vitsoe’s customers are discerning. They are frequently international people who have been widely exposed to the best that this world has to offer. Moreover, they are not fooled easily. Hence the manner in which we communicate with these individuals is of paramount importance to us.

To complicate matters, we need a teutonic sense of ordnung whilst longing for a splash of English eccentricity. And naturally we want to deal only with the most professional suppliers but we want to have some fun in the process; and we want to see our money spent on talent, creativity and experience – our egos do not need to be massaged by the delusion of unnecessarily excessive overheads. For many years we have worked with celebrated – and not so celebrated – graphic designers in search of a company which would be able to accommodate our strict requirements.

Fortunately, in 1993 our lifelong subscription to Design Week was justified by a single issue when we were alerted to the creation of Thomas Manss & Company. From a simple folded card (designed and printed in ten days) we have progressed through a series of complex technical literature (lots of ordnung), via award-winning exhibition design, to arrive at our most recent project together – the sexy bit. And what fun we have had. 36 colour pages photographed in numerous locations, produced on-time, to-budget and now bringing home the results. As the photographer Ken Kirkwood subsequently commented, “Its final success is due almost entirely to the symbiosis of like minds.”

The pundits tell us that Thomas Manss & Company does not fit into a recognisable graphics category. We can see why. Where else can one find such impeccable Englishness in a German who lives and works in London and Berlin, and manages to possess the virtues of both cultures without the vices? Perhaps it is the process of Fletcherisation on a receptive German mind that yields such fruitful results.

Mark Adams

Organised

Things are very organised. Dieter Rams' Vitsœ shelving lines the walls: The floor is occupied by big five-legged drawing-office tables ... around which everyone sits on bent-plywood chairs with caster bases. His Berlin office has these chairs, too.

Quality

It is a pleasure to be working together on so many nice projects and the quality and timing of the materials you delivered is as always very very good.

Quiet

Nobody could accuse Thomas Manss of ‘quiet’ design.

Read more …

Numero Uno.

Simon Heptinstall examines current thinking on letterhead design.

The Design council spokeswoman laughed when I explained that I wanted to speak to letterhead experts. “I wonder if there is anyone who doesn’t mind being associated with that,” she scoffed. “It must be quite a limiting field.” Ironically, she promptly faxed me a list of contacts on Design Council stationery – which features a three-deck, 24pt, 18-word slogan right across the top of the page. Nothing limiting about that.

“It’s simple, effective and appropriate,” said Aziz Cami. “It’s a manifestation of what the Design Council does: galvanise, orchestrate and evangelise. They are a special organisation which has been radically re-shaped. Their letterhead needs to challenge conventions. “The easiest thing to do would have been to come up with a fancy twisted logo – but a letterhead can do so much more than look clever. The role for a letterhead as a variable campaigning headline is new. Different businesses have used varied colour schemes for different letters but nothing like this. And they can change the words in six months time if they want to be lower key or tackle a single issue.” So is this likely to launch a new fashion? Cami predicts that…clients will increasingly demand effectiveness not decoration. Justus Oehler agrees that the trend is, in effect, away form trends. “Ultimately, we give people what they need. We’ve managed to avoid the extremes of fashion to create longer-lasting designs. Their letterheads are about reliability, timelessness and correctness,” he explains. That’s the sort of attitude that riles Michael Wolff. He says that designers should aim to elevate client’ aspirations. “The trend is that people are timid at the moment. They’re worried someone won’t like their letterhead. But these big companies are generally constipated. We as designers have to put them in touch with their true potential. Huge companies can have lovely letterheads, like Apple Computers for example.”

Wolff, who I disturbed as he wrote to thank his dustman for a good year’s service, says most letters are “staggeringly dreary”. “Some design companies write to me and their letters manage to look and read like something from an 18th-century solicitor. With all today’s digital sophistication, most letters still look like they were produced on a turn-of-the-century typwriter. Terence Conran wrote to me years ago when I had asked for some money for a conference or something. The letter came back an it just said: ‘Dear Micheal, No, Terence’ in huge type. It was very elegant. I have never forgotten it That’s where the Design Council’s new letterhead can score,” says Wolff. “They could say something different to individuals in that headline style. For example, it could say in big type: ’Dear Michael Wolff, Can I have my cheque please?’, then the rest of the letter underneath in normal size.”

Nobody could accuse Thomas Manss of “quiet” design on the evidence of his letterhead for Laserbureau. This colour printing business tops its letters with a bright pattern of seemingly random words that, on second glance, reveal a message. The design is generated on an Apple Mac with Adobe Illustrator software and can be manipulated to highlight particular words. Particular services can be emphasised when appropriate. “Five years ago, the artwork alone would have taken hours to produce, not to mention the cost of printing,” says Manss. “Now with Macintosh technology and Laserbureau’s own facilities, it is a very practical solution.”

John Gorham is another designer who believes the trend is towards individualistic design. “If I knew what the fashion in letterheads was, I would react against it,” he said. “My images come from solving the problem. I create my own fashions.”

Simon Heptinstall

Reputation

Manss has got a bit of a reputation as a book designer. Not surprisingly, given that his books are so good.

Single-minded

If Thomas Manss & Company’s work shows a certain single-mindedness, it is no contradiction that it is exemplary in its diversity.

Surprise

Thomas Manss & Company are good at designing anything: logos, brochures, annual reports, exhibitions, books, magazines and websites. The design formula remains unchanged: it's a combination of logic and surprise.